On February 17th, 1864, the H. L. Hunley became the first successful combat submarine in world history with the sinking of the USS Housatonic. After completing her mission, she mysteriously vanished and remained lost at sea for over a century. For decades, adventurers searched for the legendary submarine. Over a century later, the National Underwater and Marine Agency (NUMA), led by New York Times-bestselling author Clive Cussler, finally found the Hunley in 1995. News of the discovery traveled quickly around the world. A ground breaking effort began to retrieve the fragile submarine from the sea. The Hunley Commission and Friends of the Hunley, a non-profit group charged with raising funds in support of the vessel, led an effort with the United States Navy that culminated on August 8th, 2000 with the Hunley’s safe recovery.

She was then delivered to the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, a high-tech lab specifically designed to conserve the vessel and unlock the mystery of her disappearance. The conservation center is located on the old Naval Station in Charleston. The building is owned and research is conducted by Clemson University. The Hunley has since been excavated and proved to be a time capsule, holding a wide array of artifacts that can teach us about life during the American Civil War. The submarine and the hundreds of artifacts found onboard are currently undergoing preservation work while archaeologists use the historical clues they have found to piece together the final moments of the Hunley and her crew.

At the outset of the Civil war, the Union recognized the importance of keeping the Confederacy isolated from foreign markets. Their goal was to close all Confederate ports, preventing ships from exporting goods in support of commerce or delivering cargo and supplies to the South. Once in place, the Union’s Blockade strategy was very effective, covering 3,500 miles of coastline and 12 major ports. It was literally starving the South of supplies. The South grew increasingly desperate for any way to break the blockade to bring in much needed supplies.

The newly formed Confederate States of America had to rethink traditional battle tactics at sea when up against the powerful and established Union Navy. Born out of necessity, this setting led the Confederates to make groundbreaking advancements in naval warfare and eventually led to the building of the world’s first successful submarine. The H. L. Hunley story begins here when Horace L. Hunley, James McClintock and Baxter Watson began to work together to find solutions to break the blockade. They attempted to take the battle beneath the water’s surface and built a series of experimental underwater vessels, and helped give birth to the age of the submarine.

McClintock and Watson were in the steam gauge manufacturing business in New Orleans and locally noted for their talent in engineering and design. These two inventors began the construction of a three-man underwater boat. During the early phases of construction another Louisiana gentleman eagerly joined McClintock and Watson in their underwater venture. Horace L. Hunley, would eventually walk many paths in his life but most notably, submarine innovator and financier. The small band of Confederates began work on a new approach to naval warfare, one that took the fight below the water’s surface. This quest became a process of innovation and evolution. Hunley, Watson and McClintock developed two prototype submarines, the Pioneer and the American Diver. Improving the concept each time, they finally had success with the creation of the Hunley, a weapon that would forever change naval warfare.

The Pioneer was built in New Orleans in early 1862 and performed moderately well. After only a short month of tests, the Pioneer was destroyed by the Confederates to avoid capture by the Union army that was quickly closing in on the city. Union occupation forces were entering New Orleans when the three inventors, carrying blueprints, diagrams and drawings, fled to Mobile, Alabama, with the intent of designing an even more formidable submersible attack boat. Soon after arriving in Mobile, McClintock, Watson, and Hunley teamed up with Confederate patriots Thomas Park and Thomas Lyons, owners of the Park & Lyons machine shop. Within months after Hunley, McClintock, and Watson arrived to the besieged and blockaded Alabama coast, a second submarine was already under construction at the Park and Lyons shop near the harbor. During this timeframe, the group began to receive local military support. Lieutenant William Alexander, CSA, of the Twenty-First Alabama Volunteer Regiment, was assigned to duty at Park & Lyons. The group of engineers made several attempts at propelling the new sub with an electric-magnetic engine or a small steam engine. Unfortunately, they were unable to produce enough power to safely and efficiently propel the submarine. This “trial and error” process took place over a period of several months until they decided to stick with a more conventional means of propulsion. They installed a hand crank and, by mid-January 1863, the American Diver was ready for harbor trials.

The American Diver, according to McClintock, was “unable to get a speed sufficient to make the boat of service against the vessels blockading the port.” Despite the American Diver’s apparent limitations, evidence exists that indicates she left from Fort Morgan sometime in mid-February and attempted an attack on the blockade. The attack was unsuccessful. Soon after, another attack was planned, but as she was being towed off Fort Morgan at the mouth of Mobile Bay in February of 1863, a stormy sea engulfed the American Diver. Fortunately, no lives were lost. The American Diver was never recovered, and her rusting hull may still remain beneath the shifting sands off the Alabama coastline. Her exact location was long ago lost by history.

McClintock, Watson and Hunley did not linger over the loss of the American Diver. With their funds exhausted, they quickly found investors for their submarine concept in an organization of Confederate engineers, referred to as Singer’s Secret Service Corps. They returned to their plans, confident in their ability to create a vessel that would succeed. Taking the lessons learned during test missions of the Pioneer and American Diver, work began on a new submarine. Once again working out of Park and Lyons Machine Shop in Mobile, the team began to build anew. The third submarine was referred to by some as the “Fish Boat” or the “Fish Torpedo Boat”, but would ultimately be named for her committed benefactor, H. L. Hunley.

While the H. L. Hunley began her preliminary testing, the news of the defeat at Gettysburg and loss of Vicksburg had reached Mobile. Times were increasingly desperate for the Confederacy. The Hunley was initially designed to dive completely below her target while towing behind a floating torpedo on a 200-foot tether. Once the submarine dove and passed under the keel of her target, the torpedo would impact its hull on the other side, in theory causing a devastating explosion that would sink the ship. To safely dive under a Union vessel, the Captain would need to carefully maneuver the five-foot tall submarine between the ocean bottom and the keel of the target ship. Satisfied with their submarine’s performance, in July 1863, a demonstration of the Hunley’s attack capabilities took place for Confederate officials. An old coal-hauling barge was anchored in the middle of the Mobile River. The Hunley approached her mark and then dove beneath the target vessel. When the torpedo hit the barge, it blew up and sank within minutes. The Hunley resurfaced shortly after. After two years of attempts at the submarine concept, it had finally happened. The Hunley had successfully attacked her target. On site to witness the display were several high ranking officials including Admiral Franklin Buchanan, Mobile’s Naval Commandant. He was satisfied the Hunley could be used successfully in blowing up one or more of the enemy’s Iron Clads in the harbor. General Beauregard agreed, requesting the “much needed” fish boat be sent at once. The Hunley was loaded onto two flat rail cars and sent to defend Charleston with the hopes she could help cripple the blockade strangling the city.

The H. L. Hunley arrived in Charleston on August 12th, 1863, accompanied by James McClintock and Gus Whitney, one of the investors in the sub. The crew quickly began testing the Hunley in Charleston Harbor. Frustrated by McClintock’s pace, the Confederates seized the Hunley submarine and turned it over to Lt. John Payne, a Navy man assigned to the CSS Chicora. On August 29th, the Hunley was moored at Fort Johnson, preparing to depart for its first attack on the blockade when it suddenly sank at the dock. There are conflicting stories of what happened: Some claimed the wake of a passing ship flooded into the Hunley’s open hatches, filling it with enough water to sink it. Others claimed the mooring lines of another ship became tangled on the sub, pulling it onto its side until its hatches were underwater. Whatever happened, the result was the same: the Hunley sank immediately, taking five of her crew down to their deaths. Payne, who was standing atop the sub, jumped into the water and was rescued. William Robinson escaped through the aft hatch and Charles Hasker – trapped by the hatch cover – rode the sub to the bottom before freeing himself and swimming to the surface.

It took weeks to retrieve the submarine, and in that time Horace Hunley arrived in Charleston and demanded the submarine be returned to him. Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard granted the request, and Hunley sent for a crew of men from the Park and Lyons Machine Shop in Mobile. During her test missions in Charleston, the Hunley suffered two fatal sinkings that would claim the lives of over a dozen men, including Horace Hunley himself. On October 15th, Horace Hunley scheduled a demonstration of his boat in Charleston Harbor. He announced his vessel would dive beneath the CSS Indian Chief and surface on the other side. Once the submarine disappeared beneath the waves, it was not seen again for weeks. Bad weather delayed search efforts and divers did not recover the H. L. Hunley until November 7th. It was found deep in the harbor channel, with its bow buried in the mud and its stern still floating.

Chains and ropes were used to hoist it to the surface and place it on the dock. When its hatches were opened, there was a gruesome sight with the crew members seemingly frozen in time. Thomas Park was found with his head in the aft conning tower. Horace Hunley, still clutching a candle, was in the forward conning tower. Rescuers reported the forward ballast tank valve had been left open, allowing the submarine to fill with water. The wrench used to operate the seacock was found on the floor of the submarine leading them to theorize Hunley had either forgotten to close the valve or lost the wrench and was unable to close it. The sub’s keel weights had been partially loosened, which suggested the crew realized they were in danger, but not in time to save themselves.

Third Hunley Crew: Volunteers All. Lieutenant George E. Dixon, Arnold Becker, Corporal J.F. Carlsen, Frank Collins, C. Lumpkin Miller, James A. Wicks, and Joseph Ridgaway. Two tragedies had now befallen the H. L. Hunley. The sinkings and visible recovery efforts that followed had created quite a stir in Charleston. It was not long before Rear Admiral John Dahlgren, the head of the Union blockading fleet, learned of the diving submarine from Confederate deserters. In response, Dahlgren ordered his blockading squadron to anchor in shallow water, hang ropes and chains over their sides as defensive measures, and deploy picket craft to keep torpedo-bearing boats away. These clever tactics were also the genesis of anti-submarine countermeasures. Confederate General Beauregard was reluctant to put the Hunley back in service, writing: “It is more dangerous to those who use it than to the enemy.” Still, the submarine had persuasive backers including Lieutenants George Dixon and William Alexander, both of whom passionately believed she could be successful in breaking the blockade. Even they knew the Hunley had to be modified if she were to be successful. The Union’s anti-submarine moves coupled with the difficulty of controlling the Hunley’s depth and pitch while submerged led them to completely rethink the mode of attack.

Captain George Dixon and his volunteer crew worked aboard the H. L. Hunley an average of four nights a week between mid-December 1863 and the end of January 1864, when the weather became too rough to venture into the ocean. On many of those trips, the submarine got close enough to blockade ships to hear Union soldiers singing on the picket boats, but they never got the chance to attack. Dixon wrote to a friend expressing frustration with the conditions that stopped them from making an attack on the Blockade, “…to catch the Atlantic Ocean smooth during the winter months is considerable of an undertaking and one that I never wish to undertake again.” On a moonlit night in February, 1864, the crew of the Hunley was given the calm sea they had waited for and embarked on their ambitious attack. The target was the USS Housatonic, one of the Union’s mightiest and newest sloops-of-war. The Hunley’s approach was stealth and by the time they were spotted, it was too late. At about 8:45pm, several sailors on the deck of the USS Housatonic reported seeing something on the water just a few hundred feet away. The officer on the deck thought it might be a porpoise, coming up to blow. As the object approached the ship, the crew realized it was no porpoise. The alarm sounded and the sailors fired their guns, the bullets pinging off the metal hull of the Hunley. Below the surface, the spar torpedo detonated and the explosion blew a hole in the ship. The Housatonic sank in less than five minutes, causing the death of 5 of its 155 crewmen.

Nearly 45 minutes later, a Union sailor claimed he saw a blue light on the water. Some speculate this was the last reported sighting of the Hunley for more than a century. One record indicates Dixon had promised the troops at Battery Marshall, if successful, he would signal to shore by showing two blue lights. The Confederates on Sullivan’s Island say they saw the agreed upon signal and lit a fire to guide the Hunley home, but she never returned. Instead, the submarine and crew disappeared into the darkness of the sea. Their fate became a mystery and their accomplishment a legend. The submarine would not see the light of day again for over 136 years. As soon as the submarine was lost, efforts to find her began. The Union fleet dragged the area around the USS Housatonic wreck in hopes of snagging the little submarine. Generation after generation of explorers scoured the sea around the site of the fallen Housatonic, hoping to discover the legendary H. L. Hunley and her doomed crew. The world would have to wait until technology caught up with the search, with modern tools ultimately helping locate her.

After fifteen years of searching, on May 3rd, 1995, New York Times best-selling author Clive Cussler and his team finally found the submarine. Long interested in maritime history, Cussler founded the National Underwater and Marine Agency (NUMA), an organization that searches for some of history’s most famous shipwrecks. “I have never made claim to being an archaeologist. I’m purely a dilettante who loves the challenge of solving a mystery; and there is no greater mystery than a lost shipwreck,” said Cussler. Finding the world’s first combat submarine was a mission right up NUMA’s alley. Much like the Hunley in her mission to make world history in the 19th century, NUMA didn’t get lucky the first time. Using a magnetometer, the Cussler crew located a metal object about four miles off the coast of Sullivan’s Island. After diving in nearly 30 feet of water, they removed three feet of sediment to reveal one of the Hunley’s two small conning towers.

As if stuck in time, the Hunley lay on her starboard side with the bow pointing almost directly toward the Housatonic wreck and Sullivan’s Island. Her position looked like she was heading home, a trip that was finally about to be completed over a century later. May 3rd, 1995 - The Hunley discovered by NUMA. What Next? Once the Hunley was found, a whole new set of issues emerged: Originally built as a privateer vessel in support of the Confederacy, who owns the Hunley? If there are human remains onboard, how should they be treated? Should the submarine be left at sea as a war grave? How will she be protected from looters now that her location is known?

These questions and many more would take years to answer. It was ultimately determined the Hunley was owned by the United States government. To protect the vessel from looters and ensure the appropriate treatment of any human remains, she had to be recovered from the ocean and conserved. Given the submarine’s deep historical significance, the decision was made to put the Hunley on display as one of America’s great maritime artifacts.

Raising the Hunley from the ocean floor was a daunting task. Coordinating with the appropriate entities at the state, federal and local level required the delicate touch of someone familiar with government. Senator Glenn McConnell answered the call. He helped negotiate a contractual agreement that outlines the appropriate manner to treat the Hunley, an irreplaceable piece of American history. While Senator McConnell navigated the different government jurisdictions, someone needed to raise money and manage the actual lifting of the Hunley from the ocean floor. When Senator McConnell first asked Warren Lasch to fill this role as chairman of Friends of the Hunley in 1997, he had only one question: “What’s the Hunley?” The answer changed his life. Lasch, a successful businessman, became the driving force behind the project. McConnell and Lasch made an incredible team and together, they would achieve what many thought impossible. Bringing the Hunley back to land proved to be an engineering challenge of unprecedented proportions. Further complicating matters was the presence of human remains within the submarine. Warren Lasch spearheaded the mission, often using the mantra, “Let’s bring the boys home.”

To get the job done, he pulled together an international team of experts and partners, including the Department of the Navy, the National Park Service, Department of Natural Resources and Oceaneering International. They developed a state-of-the-art plan that required precision timing, flawless engineering, highly trained divers, perfect weather conditions and a little luck. As part of this incredible undertaking, Friends of the Hunley Chairman Warren Lasch brought together a high caliber team.

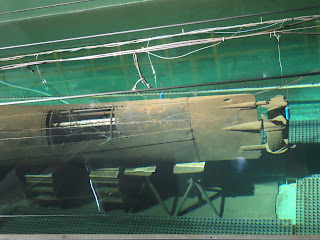

August 8, 2000 – All eyes were focused on this Southern port city to watch the Hunley – the world’s first successful combat submarine – finally return home from a voyage that began well over a century ago. The harbor was filled with on-lookers. Spectators and reporters from around the world lined the docks, watching history unfold. Just as the crew did in 1864 on the night they made world history, the recovery team waited for a calm sea for the actual lifting of the Hunley. The well-planned recovery procedure was completed flawlessly, with the historic artifact raised safely. After the Hunley broke the water’s surface, she was gently placed onto a transport barge. Support personnel stabilized the submarine with tension straps to keep her safe. She was brought to the Warren Lasch Conservation Center and placed in a 75,000 gallon steel tank filled with chilled, fresh water to help protect and stabilize the submarine. The lab facility was specifically designed to excavate and conserve the vessel.

Now that the Hunley was safe, the work of learning her secrets could begin. The groundbreaking excavation of the Hunley’s crew compartment unearthed rare 19th century artifacts, including a gold coin that saved the life of the submarine’s Captain at the Battle of Shiloh in 1862. The coin is curved from the indention of a bullet and inscribed with his initials along with the words, “My life Preserver.” The remains of the entire eight-man crew were also found resting peacefully at their stations. They were removed from the submarine and plans were immediately put in place to give them a proper burial, an event that had been impossible for over a century.

The morning was warm, and the waters off Charleston Harbor were unusually calm. It was perhaps the same sort of sea conditions Hunley commander Lt. Dixon was waiting for in 1864 when he and his crew launched the experimental vessel that began the age of modern day submarines. But this day would not mark the beginning of the Hunley crew’s mission, but rather the completion of their century long journey to a final burial. On April 17th, 2004, the submarine pioneers that manned the first successful combat submarine were buried. The ceremony began at 9:15 a.m. with a memorial service at White Points Garden. Immediately after the ceremony, horse drawn caissons followed by a procession of men and women dressed in 19th century attire brought the crew to their final resting place. The procession marched 4.5-miles through downtown Charleston, and ended at Magnolia Cemetery. The Hunley’s eight-man crew was then laid to rest next to others who lost their lives on Hunley test missions.

The burial was attended by tens of thousands of people who came to honor the crew and witness this historic moment. Visitors came from around the world, including Australia, Germany, France, and Great Britain. The funeral procession along East Bay St., Charleston, SC. Additionally, the Friends of the Hunley research team was able to locate descendants of two of the crewmembers, and they participated in the burial of their ancestors. The attendance of crewmember descendants and the overwhelming amount of visitors made the burial not just a solemn and inspirational event, but a celebration of our nation’s history. Now, at last, they were at rest. The attendance of crewmember descendants and the overwhelming amount of visitors made the burial not just a solemn and inspirational event, but a celebration of our nation's history.